Fundraising isn’t all about numbers and pitch decks. Instead, there’s also a number of legal terms and clauses you’ll need to understand before you can actually sign a term sheet and raise money from investors for your startup.

Term sheets can be intimidating at first, especially if this is your first round. Yet, having a good idea of what are the key terms and clauses to look out for when negotiating with investors is paramount. Indeed, your term sheet will have a major impact on your startups’ future rounds, from equity ownership, governance & control, investors’ rights and exit.

In this article we’ll cover all the key terms you should know before raising investor money. That way, you’ll be in a better place to make the best decisions out of your future fundraising rounds.

What’s a Term Sheet?

Before we dive into the key terms and clauses of a startup term sheet, let’s first define what it actually is.

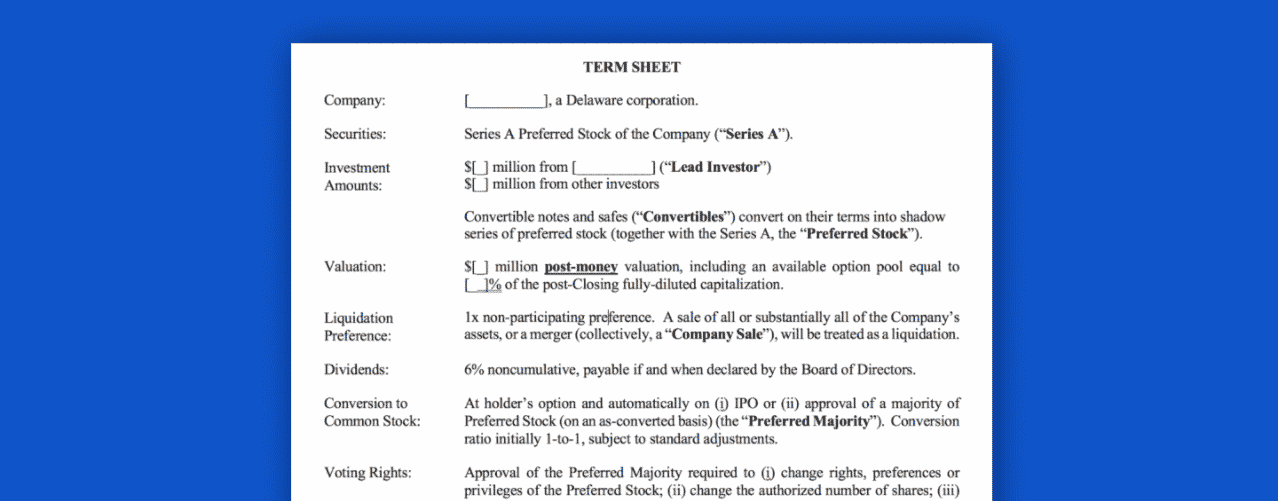

A term sheet is a legal document that defines the terms and conditions of an investment into a business. For startups, by term sheet we often refer to a equity round term sheet. Yet, debt term sheets also exist (e.g. convertible notes).

Note: for the purpose of this article, and to avoid any misunderstanding, we will be discussing a standard equity round term sheet main terms and clauses.

A term sheet is a non-binding document: it serves as a first step for new investors and existing investors to agree on key terms before actually drafting the binding legal documents. As such, a term sheet usually includes terms around:

- the agreed valuation of your business

- the total investment amount

- the type of shares investors will receive, and the rights associated to them

Also, a term sheet is most often negotiated by the lead investor coming into the deal. A lead investor is the most sophisticated and typically the largest investor (e.g. a VC fund) that negotiates key terms so that other investors can agree (or not) on the terms and invest alongside the lead investors.

So why startups receive multiple term sheets?

One common question that we often get is why do we mention multiple term sheets for one round if there should be only one?

After pitching an investor, a startup that made a great impression may receive a term sheet proposition. Therefore, if you pitch 10 investors that want to come into the deal, you might get 10 different term sheet proposals.

These are simply propositions from the investors. As you would imagine, the more the better as it allows you to compare terms and be in a better place to negotiate later on.

The term sheet you will finally agree with before signing binding documents will be the result of negotiations with the lead investor‘s term sheet you would have chosen.

Of course, your ability to deviate from the lead investor’ term sheet proposition depends on your bargaining power: how many other term sheets you’ve received, and how advantageous they are for you.

Key Terms: Equity Ownership

There are 4 main sections within a startup equity term sheet, each with their own key clauses:

- Equity ownership

- Investors’ rights

- Governance & control

- Exit & liquidity

Let’s start here with equity ownership.

Equity ownership clauses are a critical part of a term sheet defines your business valuation, and consequently how much new investors will get as part of the round, and how much you should give (dilution).

Also, they define future valuations, and how investors’ respective equity interest varies in future rounds.

1. Pre- and Post-Money Valuation

Pre- and post-money valuation refers to the actual value of a company as part of the round.

Pre-money valuation is the valuation of a company before it raises capital. By establishing a pre-money valuation, it allows new investors to set the amount of equity they will receive in exchange for their capital. In parallel, it allows existing investors and founders to understand their dilution of ownership by selling part of the capital to the new investors.

Post-money valuation, in turn, is the value of a business after the funding round. Logically, if a company’s pre money valuation is $10 million and it raises a $4 million round, post-money valuation is $14 million.

For a detailed explanation on what pre and post-money valuation are, and how they impact equity ownership, read our article here.

2. Liquidation Preference

Liquidation preference rights define how and when preferred stock investors can sell their investment.

Preferred stock is a type of equity with preferential treatment over common stock. Preferred stock shares are often issued to early-stage investors in return for their investment which is, logically, more risky because early stage.

Liquidation preference is a clause within the term sheet that define the priority preferred stock investors will have over common stock investors when exiting their participation.

There are 3 types of preferred stock:

- Non-participating preferred stock: when the business is sold, preferred stockholders are entitled to a multiple of their initial investment as proceeds. The distribution happens before any distribution to common shareholders (thereby preferential treatment)

For example, if the multiple is 3x and a preferred stockholder invested originally $100,000, the investor gets back $300,000.

- Participating preferred stock: at exit, preferred stockholders get the return of their initial investment first, plus a share of the proceeds left after all preferred stockholders have been paid, like any other common stockholder. Effectively, preferred investors are paid twice, as preferred investors (first payout) and common investors (second payment)

For example, let’s assume:

- 1 preferred stockholder only that invests $500,000 for 10% of the company

- The business is sold for $20 million

The investor gets back $2 million first, and then $1.6 million for 10% of the remaining $18 million.

- Capped participating preferred: at exit, preferred stockholders get the return of their investment, plus a capped share of the proceeds left to common stockholders. Capped participating preferred is therefore a compromise between the 2 methods discussed above

3. Conversion Rights

Conversion rights allow preferred stockholders to convert their preferred shares into common shares if they wish so.

Sometimes it makes indeed more sense for preferred stockholders to participate in the common stockholders’ share of proceeds at exit. This makes sense especially when the liquidation preference clauses aren’t favorable to preferred stockholders.

4. ESOPs (Employee Stock Option Pools)

ESOP (short for “Employee Share Ownership Plan“) is a pool of options you reserve to issue to your employees (or some of your employees) in the future.

Companies use ESOP shares to align the interests of their employees with those of their shareholders (the founders, VCs and angel investors for startups).

Before each fundraising round, investors will ask you to either create an ESOP (for the first round) or increase that pool. Most startups typically have 10-15% of total shares as the ESOP pool.

Because the ESOP is created out of the pre-money valuation, only existing investors get diluted as part of the creation (or increase of the existing ESOP). You want to make the ESOP large enough to make sure all new hires get the ESOPs they deserve, yet not too much to get too diluted either.

5. Dividends

Dividends is a payment made up from the distribution of profits from a company to its shareholders. Like any other company, startups can distribute dividends too, provided profits are positive of course.

There are 2 types of dividends:

- Cumulative: dividends are calculated each year and, if not paid, are carried forward to future years to be paid

- Non-cumulative: dividends that aren’t paid in a given year are cancelled and can’t be carried forward to be paid in the future. This is the best option for founders as it limits the risk of having to pay substantial dividends to investors at exit, on top of their initial investments returns

Key Terms: Investors’ Rights

Investors’ rights are a set of clauses that define investors’ investment protection.

6. Anti-dilution Rights

Anti-dilution rights protect preferred stockholders from a “down round”. A down round is a situation where a business raise capital at a lower valuation than the previous round.

In a down round existing investors get further diluted from the investment of new investors. Let’s use an example to understand this better:

- A business raise a Seed I at a $10 million valuation

- Preferred investors put in $2 million in return for 20%

- The business later does rather poorly and raise a Seed II round at $8 million valuation

In such situation, new investors that chip in $2 million would now get 25%, more than preferred stockholders who came earlier.

To avoid such situation, anti-dilution rights give preferred stockholders additional shares to prevent dilution in a down round.

7. Pro-rata Rights

Pro-rata clauses in term sheets give investors the option to participate in future funding rounds to maintain their current percentage ownership.

As such, existing investors have a preferential treatment. Indeed, they’re asked whether they want to come into future deals before new investors actually chip in. If they choose not to, they’d be logically diluted.

8. Right Of First Refusal

Right of first refusal (“ROFR”) is a clause whereby existing investors have a preferential right to buy stock from a selling investor. Along with the “approval of sale” clause, ROFR protects investors from secretive transfers of ownership, especially to competitors.

9. No-shop Clause

A no-shop clause is a clause you’ll only see in a term sheet (and not in the actual binding documents). Indeed, the no-shop clause is a commitment from both founders and the lead investor to get the deal done within a reasonable period.

Usually from 30 to 60 days, founders and existing investors agree not to “shop” the deal with someone else. The lead investor instead agrees to do the work within the agreed timeline (i.e. due diligence).

Key Terms: Governance & Control

Governance clauses regulates who actually is in control of the business, and who makes certain decisions.

10. Voting Rights

Voting rights give shareholders the right to vote for certain corporate actions.

In term sheets, voting rights define how many voting rights each instrument has (shares A, B, preferred, etc.). They also define which corporate action requires a majority vote, and what majority vote actually is (> 50% or more).

Voting rights give shareholders rights to opine and/or block certain actions such as: payment of dividends, budgets approval, number of board members, etc.

11. Protective Rights

Protective rights are granted to preferred stockholders and help protect investors from majority stockholders. Preferred stockholders have the right to veto certain action, even authorized by the Board of Directors.

There are multiple provisions preferred stockholders can veto. There are 2 types of provisions: standard and non-standard protective provisions.

Whilst standard provisions are usual for any deal, non-standard protective provisions include specific decisions that preferred can veto. Therefore, the more non-standard provisions, the more power preferred stockholders have.

As a founder, you should be wary to limit the excessive power that may be granted to preferred stockholders as part of protective rights.

12. Board Rights

The board rights are given to the board of Directors. The Directors themselves are selected by the investors to represents all the shareholders’ interests at the board meetings.

A term sheet typically include a set of clauses that either define (first round) or adjust (subsequent rounds) the structure of the Board of Directors (the number of seats) and the frequency of the board meetings.

Understanding board rights is paramount because of the power Directors may have. If as a founder or large investor you lose control over the Board, you may very well lose control over the company itself, even if you’re the largest investor.

13. Information Rights

Information rights command how frequent and what details should include the financial reports to investors. Some startups report to investors monthly, yet not all do.

Of course, annual management reports (and sometimes quarterly) are usually required by law at the end of the fiscal year.

14. Founder Vesting

Founder vesting regulates how and when founders can leave the company, by impacting the shares they actually hold. Common practice is to have 4 years schedule, with 25% of your shares vesting after the first year, and 36th each month after that.

Key Terms: Exit & Liquidity

Exit and liquidity clauses set the conditions around investors’ payouts in an exit scenario.

15. Drag-along & Tag-along Rights

Drag-along rights prevent minority shareholders from blocking the sale of the company to an external investor, as long as it has already been approved by the majority shareholder. As such, drag-along rights are typically in favor of majority shareholders and founders.

Tag-along rights, in comparison, benefit minority shareholders. It oblige the majority shareholder to include the minority shareholders in negotiations. For example, if a majority shareholder sells its share to a new investor, minority investors have de facto the right to join the transaction as well.

16. Redemption Rights

Redemption rights are given to preferred investors. It allow them to require the company to repurchase shares from them at a specified point in time.

Redemption rights protect preferred stockholders from the sub-optimal sale of the company (e.g. low price).

They’re a rather rare term sheet clauses as 1 out of 3 startup term sheet include redemption rights. This for the simple reason that most startups don’t have the cash to buy back investors’ shares as they’re often loss-making.

Yet, redemption rights can be very dangerous too. Indeed, management may be forced to quickly sell the company to be able to pay back preferred stockholders for example.

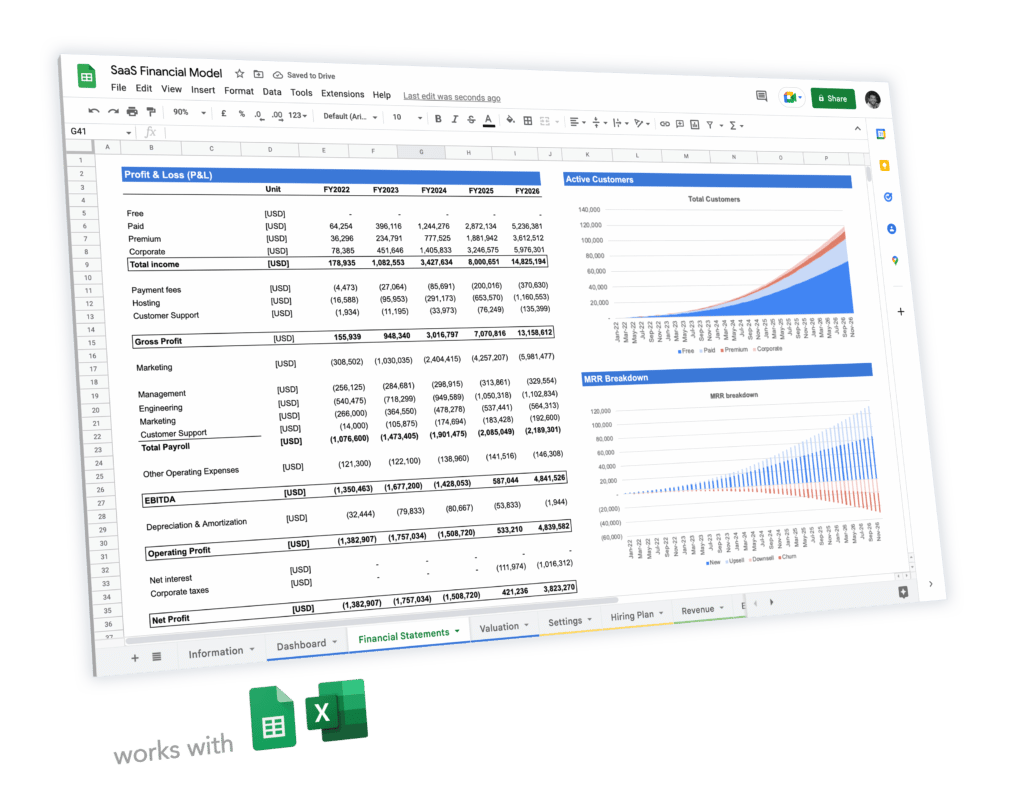

5-year pro forma financial model

5-year pro forma financial model 20+ charts and business valuation

20+ charts and business valuation  Free support

Free support