When you negotiate your term sheet with investors, make sure to carefully read between the lines and avoid red flags. There are number of clauses that you want to push back on at all costs.

Often, red flags are excessive provisions within legal documents that result in overly favorable terms for pref investors, to the detriment of founders and common shareholders.

In this article we will go through the top 5 red flags you should avoid when negotiating a term sheet for your startup. This will allow you not only for you to get the best deal out of your funding round, but also for your startup as some may have dangerous consequences.

Let’s dive in!

What’s A Term Sheet?

A term sheet is a legal document that defines the terms and conditions of an investment into a business. For startups, by term sheet we often refer to a equity round term sheet. Yet, debt term sheets also exist (e.g. convertible notes).

Note: for the purpose of this article, and to avoid any misunderstanding, we will be discussing a standard equity round term sheet main terms and clauses.

A term sheet is a non-binding document: it serves as a first step for new investors and existing investors to agree on key terms before actually drafting the binding legal documents. As such, a term sheet usually includes terms around:

- the agreed valuation of your business

- the total investment amount

- the type of shares investors will receive, and the rights associated to them

Also, a term sheet is most often negotiated by the lead investor coming into the deal. A lead investor is the most sophisticated and typically the largest investor (e.g. a VC fund) that negotiates key terms so that other investors can agree (or not) on the terms and invest alongside the lead investors.

For a full list of the key terms and clauses you should know in your startup term sheet, have a look at our guide here.

Term Sheet Red Flag 1: Participating Preferred Stock

When looking for red flags within your term sheet, first look for participating preferred stock.

Liquidation preference is a clause within the term sheet that define the priority preferred stock investors will have over common stock investors when exiting their participation.

Preferred stock is a type of equity with preferential treatment over common stock. Preferred stock shares are often issued to early-stage investors in return for their investment which is, logically, more risky because early stage.

There are 3 types of preferred stock liquidation preference clauses:

- Non-participating preferred stock: when the business is sold, preferred stockholders are entitled to a multiple of their initial investment as proceeds. The distribution happens before any distribution to common shareholders (thereby preferential treatment)

- Participating preferred stock: at exit, preferred stockholders get the return of their initial investment first, plus a share of the proceeds left after all preferred stockholders have been paid, like any other common stockholder. Effectively, preferred investors are paid twice, as preferred investors (first payout) and common investors (second payment)

- Capped participating preferred: at exit, preferred stockholders get the return of their investment, plus a capped share of the proceeds left to common stockholders. Capped participating preferred is therefore a compromise between the 2 methods discussed above

Why is it a red flag?

Participating preferred stock give the right to preferred stockholders to be paid twice. Therefore, participating preferred stock reduces the returns of common shareholders.

This may be a problem down the road for subsequent rounds. Indeed, preferred stockholders often are early stage investors. Investors coming later often are “common shareholders”.

As an common investor, investing in a company that overly benefits preferred shareholder may dissuade you to invest altogether.

Instead of agreeing to participating preferred stock in your term sheet, try negotiating capped participating preferred stock instead (see above).

For more information on liquidation preference and its impact on exit proceeds for founders and investors, read our article here.

Term Sheet Red Flag 2: Liquidation Preference > 1x

As explained above, liquidation preference is a form of preferential treatment for preferred stockholders at exit.

At exit, preferred shareholders get (at least) a return of their investment times a multiple.

Why is it a red flag?

Let’s assume a multiple of 3x and a preferred stockholder who invested originally $100k. At exit, the investor gets back $300k.

What’s more is that the $300k reduces the share of proceeds left to common shareholders by the same amount.

Logically, the multiple needs to be viewed in light of whether preferred stock is participating, non-participating, or capped. Yet, as rule of thumb, any multiple above 1x is viewed as aggressive.

The same problem happens here: common shareholders will be reluctant to invest in the future if preferred stock investors’ liquidation preference multiple is too high.

Term Sheet Red Flag 3: Non-standard Protective Rights

Protective rights are granted to pref stockholders and are meant to protect investors from majority stockholders. With protective rights, preferred stockholders have the right to veto certain action, even authorized by the Board of Directors.

There are multiple provisions pref stockholders can veto. Some are standard and don’t require negotiation, and others are by definition “non-standard”.

Why is it a red flag?

Non-standard protective provisions include specific decisions that preferred can veto. Therefore, the more non-standard provisions, the more power preferred stockholders have.

If there are too many non-standard protective rights, it may give excessive powers to preferred stockholders and seriously limit founders’ control over the business.

A few examples of non-standard protective rights that may be a problem are:

- Prevent raising debt or any type of financial liability

- Hire and / or dismiss management

- Modify management’s compensation packages

- Purchase or sale of assets

- Change main business activity / business model

Term Sheet Red Flag 4: Full Ratchet Anti-Dilution Clause

Full ratchet anti-dilution is one of the most important red flags in a term sheet for founders.

Anti-dilution rights protect preferred stockholders from a “down round”. A down round is a situation where a business raise capital at a lower valuation than the previous round. In such situation, existing investors get further diluted from the investment of new investors.

To avoid this, anti-dilution rights give preferred stockholders additional shares to prevent dilution in a down round.

Yet, there are 2 types of anti-dilution clauses:

- Weighted average: the number of additional shares is the function of a number of parameters. It takes into account both the lower price and actual number of shares issued in the down round to new investors. That way, the adjustment is fair to both founders and pref investors

- Full ratchet: this is the most aggressive anti-dilution clause adjustment. With full ratchet, the new shares are issued at the lowest price at which the stock was issued after the preferred investor’ stock issuance, regardless of the number of shares.

Why is it a red flag?

Full ratchet anti-dilution is very aggressive and disadvantageous to founders vs. pref. investors.

Because the clause only protects pref shareholders, and not founders necessarily, full ratchet can significantly reduce founders’ ownership and interest. New investors in comparison might see a full ratchet provision as unfair. Yet, they don’t suffer from any dilution, they are merely not receiving the additional shares that pref investors do.

Therefore, full ratchet may deter some potential new investors from investing in the company, yet the burden really lies with founders.

Term Sheet Red Flag 5: Cumulative dividends

When looking for red flags within your term sheet, look for cumulative dividends.

Dividends is a payment to shareholders, as a distribution of a business’ profits. Like any other company, startups can distribute dividends too, provided profits are positive of course.

There are 2 types of dividends:

- Cumulative: dividends are calculated each year and, if not paid, are carried forward to future years to be paid

- Non-cumulative: dividends that aren’t paid in a given year are cancelled and can’t be carried forward. This is the best option for founders as it limits the risk of having to pay substantial dividends to investors at exit, on top of their initial investments returns

Why is it a red flag?

Cumulative dividends can significantly impact cash flow at exit, which might be a major red flag for potential buyers. Indeed, the buyer may have to fund a significant amount of cash upfront to pay dividends to existing investors when buying the company.

This will either result in a lower price for the exit (to net off the dividends) and/or buyers turning down the deal.

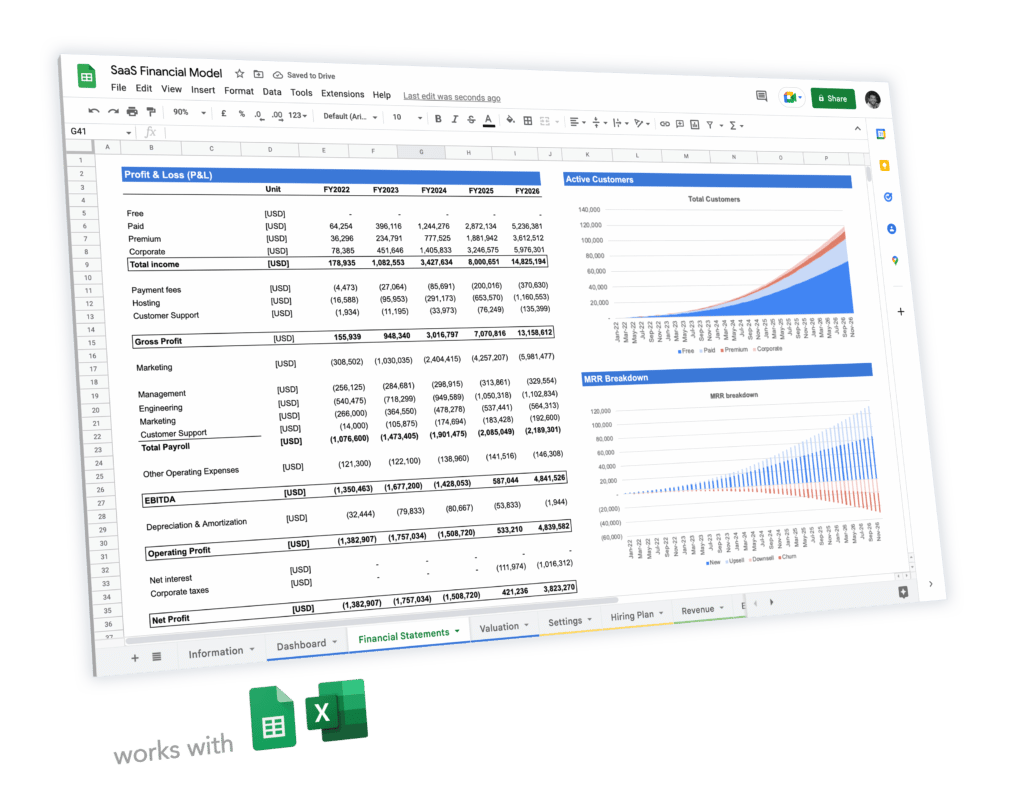

5-year pro forma financial model

5-year pro forma financial model 20+ charts and business valuation

20+ charts and business valuation  Free support

Free support