How Investors (Really) Value Startups: Pre-revenue to Series A+

A lot has been written about how to value startups. Most articles out there will list all the possible methodologies available to assess a startup’s valuation but they often miss 2 important things:

- Startup valuation methodologies are merely the start of a negotiation ; and

- They don’t necessarily work for all startups

In this article we will explain what are the methods venture capital firms and angel investors use to value startups. We’ll also look at their pros and cons, and which one you should use for your startup. Let’s dive in!

Why do we even value startups?

We often value a startup’s capital when it raises money from investors. Indeed, we need to understand the percentage of ownership which will be sold by existing investors in return for the amount of capital raised.

Indeed, if you raise equity from investors for your business, you will have to sell part of your business’ ownership at the same time.

For instance, if you raise $1M and agree on a post-money valuation of $5M, you will have to sell 20% of your equity to new investors ($1M / $5M).

That’s why founders, existing and new investors are all doing the same exercise. Each party (existing and new investors) indeed want to get the best deal out of the transaction.

Existing investors tend to have a higher valuation to decrease the percentage of equity they would have to sell. Instead, new investors tend to have a lower valuation in mind to maximise the percentage ownership they will get.

Yet, we also value startup for a number of other reasons, for example:

- Existing investors sometimes require to go through a third-party valuation assessment (by an accounting or financial advisory firm for instance) when they decide to grant stock options to employees for example

- Less often, startups can also require third-party valuation audit when raising debt from lenders for their collateral and risk analysis purposes

What drives a startup valuation?

All methodologies, although different in how they value a startup, are the quantitative result of qualitative factors. These factors drive either up or down valuation (and the valuation multiple) based on the business’ own factors positioning.

- Traction: traction is absolute (number of users for example) and relative (the monthly percentage growth or new users for instance). The higher the traction, the higher the valuation

- Execution track record. Also referred to as “reputation”, a startup valuation is higher if the founding team has a successful track record. For instance, if the CEO already founded and exited a business in the past, investors will give more credit to it. Indeed, even the best ideas can fail without great execution. Proving investors you have already done it in the past can go a long way

- Minimally Viable Product (MVP): your startup will be more valuable if you already built a MVP

- Product market fit. Investors will see favourably your startup if you can prove them you already found early adopters for your product, or even better, you already generate revenues

- Market. Your startup will be more valuable if your market is large and/or highly fragmented and/or growing at double digits

- Bargaining power of investors. If you are desperate for cash and investors are difficult to attract, valuation will suffer accordingly. In comparison, startups that can put different investors’ offers in competition will get the best deal: a higher startup valuation and a lower equity dilution percentage

Why don’t common methodologies work?

Mature companies (vs. startups) are valued using the very same methodologies by investors worldwide. Yet, because they are more stable, the valuation methodologies we use to value mature companies are far more reliable vs. when valuing startups.

That’s why all valuation methodologies for mature businesses are purely mathematical: they are a function of a financial metric.

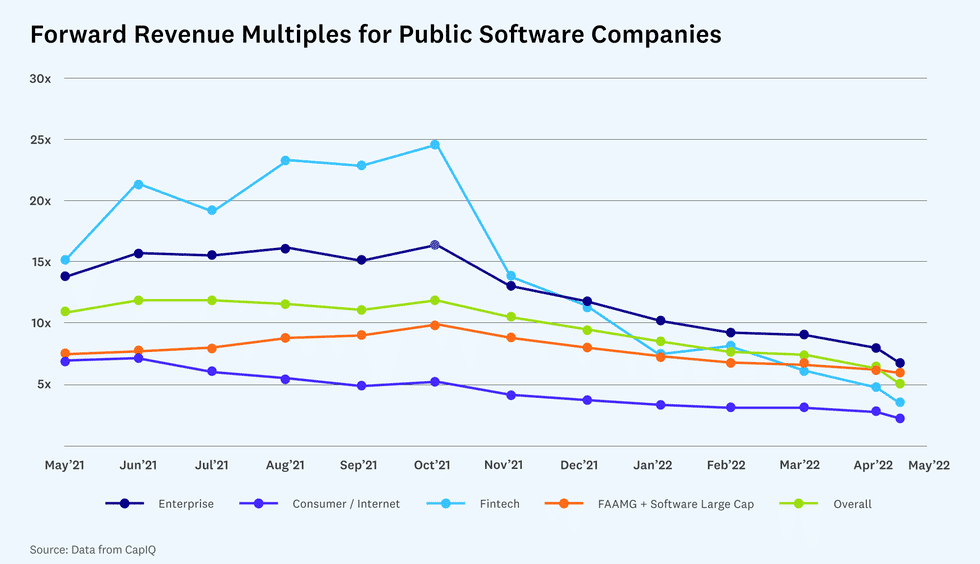

The most common methodology is the multiple valuation: we calculate valuation based on a business’ yearly financial metric (revenues or EBITDA for example), and we apply an industry average multiple.

For example, if we value a retail business with $20 million EBITDA in 2021, and apply a 12x multiple, its valuation is: EBITDA x multiple = $20M x 12 = $240 million

Unfortunately, most common methodologies don’t work for startups. This is due to 3 reasons:

- Startups are high-growth, hence their financial metrics change quickly over time. If a startup has $500k revenue in their 2nd year of operations, it might as well have $2M in revenue in their 3rd year.

- Startups are rarely profitable in their first year of operations. You can’t value a business using a negative EBITDA or net profit. That’s why we (almost) always use revenue when valuing startups using the multiple approach

- Startups sometimes don’t have any financial metric at all. If you raise capital but do not have any revenue yet, how can you value your business? It’s simply impossible. Read our article on how to value a pre-revenue startup for more information

How to value Seed startups?

A pre-seed or seed startup often have limited financial performance and a significant amount of risk. This makes it very challenging to agree on a valuation for such early stage startups. They often have no revenue and sometimes not even a MVP or a complete founding team.

For pre-seed and seed startups, investors use 2 methodologies: the Venture Capital and the Berkus methodology.

Method #1: Venture Capital Method

Post-money valuation = Terminal value / Expected return

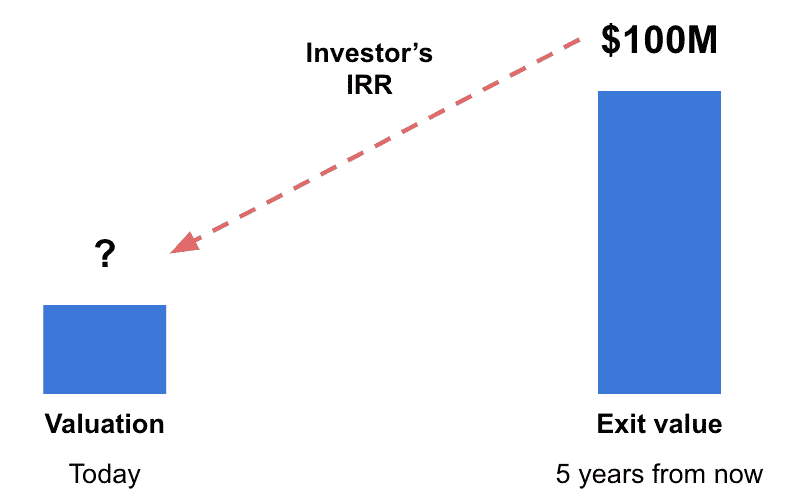

With this method, investors calculate a startup valuation based on their anticipated financial return.

Indeed, angel investors and seed VC firms (those that typically invest in early stage startups), like any other investors, aim to make a profit by selling their shares in the future at a premium.

In order to determine pre and post-money valuation investors use this formula where Post-money valuation = Pre-money valuation + invested capital.

The 2 variables are the expected return from the investor and the terminal value. The terminal value is the hypothetical value of the business in the future, when the investor plans to sell its stake.

For example, let’s assume a startup that raises $1M today. Investors estimate a terminal value of $100M in 5 years and require a 20x return on investment.

Therefore, the $100M valuation in 5 years should be $5M today for investors’ ROI to work, right? Investors are willing to invest at a $5M post money valuation today, corresponding to a 20% equity stake ($1M capital raised / $5M post money valuation)

While easy to use, the main flaw of the VC method is that it solves today’s startup valuation by taking an assumption in a future valuation (if all goes well).

Whilst venture capital firms and angels are experienced investors, the terminal value itself is very much of a guess. That’s why investors balance the Venture Capital method with the Berkus method which we are explaining below.

For more information on how to use the VC method to value your startup, read our complete guide here.

Method #2: Berkus Method

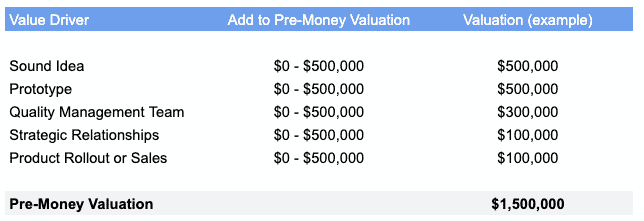

This method was created by the angel investor Dave Berkus himself. The methodology “assigns a number, a financial valuation, to each major element of risk faced by all young companies – after crediting the entrepreneur some basic value for the quality and potential of the idea itself”.

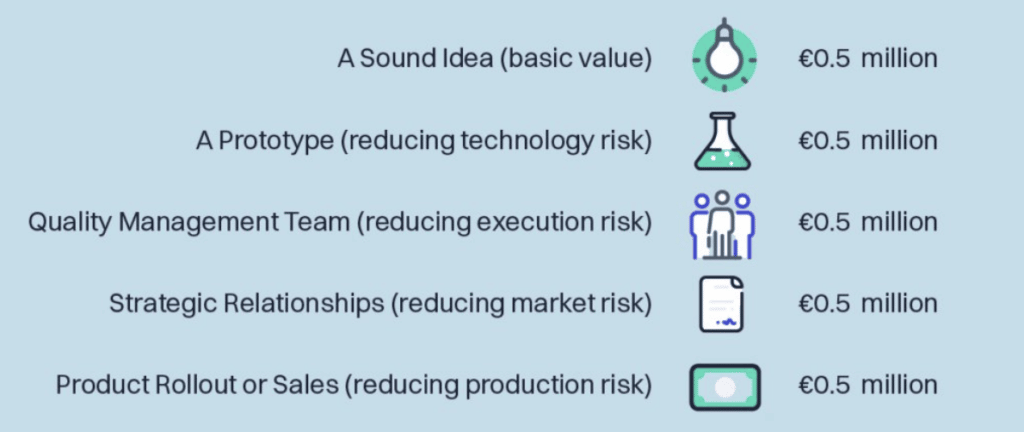

In other words, the Berkus method calculates a startup’s valuation by summing up the monetary value of each of five elements of risks, they are:

- Sound idea (basic value)

- Prototype (reduces technology risk)

- Quality management team (reduces execution risk)

- Strategic relationships (reduces market risk)

- Product rollout or sales (reduces production risk)

For each of the 5 elements, we must assign a monetary value of up to $500k. $500k is the maximum value that can be earned in each category, resulting in a maximum valuation of $2.5 million with such methodology.

Berkus Method: an example

For example, in the table we calculate an hypothetical valuation for a startup with the following assumptions:

- Sound idea: the problem the startup is trying to solve is obvious and a real pain point for many businesses / consumers

- Prototype: the startup has already developed a MVP

- Quality management team: the founding team has demonstrated experience in the sector yet hasn’t built, nor exited a startup in the past

- Strategic relationships: the startup has limited partnerships with suppliers and/or partners for marketing its product

- Product rollout or sales: the startup doesn’t have the capacity to either additional key features to the product nor selling it to customers as it needs to hire more developers and a dedicated sales team

Note that the Berkus methodology assesses a pre-money valuation: using the example above, assuming the startup is raising $1M seed, the post money valuation would be $2.5 million. An angel investor investing $1M here would theoretically get 40% ownership.

Note that the Berkus method only works for pre-revenue early stage startups. Once a startup generates revenues, investors rely on more reliable valuation methodologies which we will discuss below.

How to value Series A+ startups?

Startups that raise Series A+ funding typically has product which isn’t a MVP anymore: the startup has found product market fit and is now investing aggressively in customer acquisition. Series A startups also have complete management teams and overall a much lower level of risk vs. early stage startups.

Despite typically being high-growth businesses, Series A startups already have a lot of metrics, both operational (e.g. users) and financial (e.g. revenue, CAC, etc.). That’s why investors use the multiple methodology to value Series A startups.

Method #3: Multiple valuation methodology

The same way we value a mature business by using comparable companies (or industry average) metrics as explained earlier, investors use a multiple valuation methodology to value Series A startups.

Because comparable companies, in this case, are private companies, information is scarce. That’s why, often, venture capital firms and angel investors use revenues or the number of customers as the main multiple.

Investors use publicly information where available (Techcrunch articles, Crunchbase, press releases, etc.) to gather comparable startups’ data.

Comparable companies doesn’t necessarily need to be private. Taken with a grain of salt due to their scale, listed companies can also work very well. For an example on how to value a tech startup using the multiple valuation methodology with listed comparables, read our article here.

Method #4: Discounted Cash Flow methodology

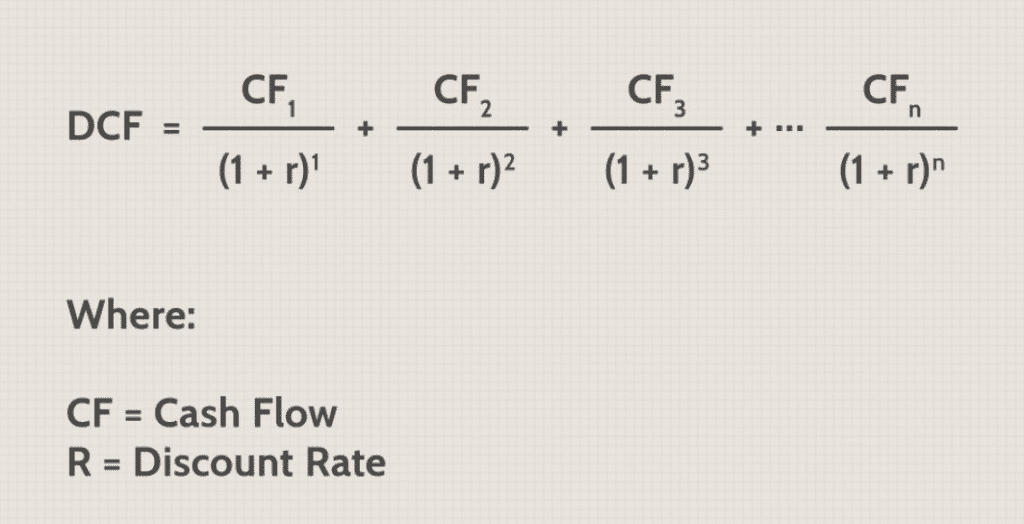

Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) is one of the most commonly used valuation methodologies. When using DCF, we estimate a business’ valuation by summing up all its expected future cash flows. The expected future cash flows are discounted using a discount rate to determine their present value.

The expected cash flows are estimated by building financial projections for the business. Existing and new investors typically discuss the assumptions behind the financial projections to agree on a DCF valuation.

The discount rate typically is the cost of capital of the business: the weighted average cost of debt and equity. Usually, discount rate ranges from 10 to 15%.

DCF can only be used for Series B startups or above. Indeed, their expected cash flows are more stable (and therefore predictable). Read our article to understand if you should use the DCF methodology to calculate your startup valuation.

How to value a pre-revenue startup?

Step 1: assess how much you need to raise

The first alternative requires you to ask yourself 2 important questions, which you will need to answer for your fundraising anyway. They are:

- How much do you need to raise?

- What percentage of the company’s equity do you want to sell?

In order to assess the amount of capital you are asking investors as part of your fundraising round, you will need to build a solid financial plan.

If you need help on how to build great projections, read our article here.

This is really important: asking too little will put you in a challenging position down the line once you have run out of cash. The opposite is also true: asking too much will create other problems too. Have a look at our article on how much you should raise for your startup for more information.

As a good rule of thumb, select the amount of capital that will give you 12 to 18 months runway. This is quite common amongst venture capital firms to fund rounds that give such timeframe. This 12-18 months window is a win-win situation. It gives founders ample room to realise their targets. In parallel it isn’t too long either for an investor to wait for them to realise.

Step 2: Decide the percentage dilution you are willing to accept

You have decided what is the appropriate amount of capital you need to raise from investors? Great. Now, you will need to decide what percentage of your company you are willing to sell as part of the round.

As a rule of thumb, most early stage startup (pre-seed and seed) raise capital at a 20% dilution percentage, or slightly less. To clarify, this means they are willing to raise a given amount of capital (say $1M) for 20% of their equity.

Logically, the higher the risk for an investor, the higher the percentage they will ask. For instance, if you are pre revenue and even haven’t launched your product yet, there is significant risks of product market fit or execution, to name a few. As such, the more prepared you are, the better deal you will get from investors. To increase your chances of getting a fair deal, come to the negotiation table with strong arguments such as an MVP, early traction, a complete founding team, etc.

Step 3: Calculate a valuation

Now that you have calculated the amount you need to raise along with the percentage of dilution you are willing to accept, we can calculate your valuation by using the following formula:

Valuation = amount raised / dilution percentage

For instance, let’s assume you want to raise $2M for a 18 months runway, and you are selling 20% to investors. Your valuation is then $10M ($2M / 20%).

Of course, valuation may vary depending on the 2 factors discussed above. Therefore, try to get a valuation range instead of a number.

Indeed, some factors might be out of your own control. Think percentage dilution for instance, you might think 10% but investors might ask for 20% instead..!

4 Proven Ways To Increase your Startup Valuation

Now that we’ve seen what are the different methodologies to value startups, let’s now have a look at how you can increase yours, either prior a fundraising round or an exit.

#1: Create Scarcity

The first factor impacting your valuation multiple is scarcity. By definition, a business that provides a scarce product and/or service means customers have few alternatives to look at. Ideally, your business is providing a product or service to your customers that no one else is able to provide.

Scarcity can take many forms. It can be due to:

- Your product is protected by intellectual property or some sort of patent that others can’t legally reproduce, giving you a technological edge

- You have strong barriers to entry, whether it is scale (e.g. you have strong organic traffic driving visitors to your website because of a high-quality, abundant content), expertise (e.g. key team members), branding (e.g. strong, memorable and positive brand name), etc.

Logically, the more scarce the product and/or service a business is selling, the higher the multiple.

Yet, scarcity isn’t necessarily resilient either: a company that loses IP protection for instance, or simply new competitors entering the market depletes scarcity, and with it, reduces the valuation multiple.

#2: Demonstrate (net + profitable) growth

It might seem obvious that the higher the growth, the higher a startup’s valuation. Unfortunately, it isn’t always the case.

If one startup can demonstrate to investors its growth is both net positive and profitable, its respective multiple will inevitably be (significantly) higher.

Net growth

Think about a SaaS business which brings in new customers every month, at a rate of 20%. This means that if they onboard 100 in month 1, they onboard another 120 in month 2, and so on.

Yet, what if the same SaaS business has an increasing churn by 20% MoM? Their customers churn faster, at a rate of +20% each month, meaning growth is null. This is a common problem for SaaS startups as the impact of churn on financials often takes months to materialise.

If not flagged on time, startups can quickly send the wrong message to investors. Their net growth (as in, net of churn) is less than what they think, and potentially negative.

Profitable growth

The same way startups can have negative net growth, they can very easily fall into unprofitable growth too.

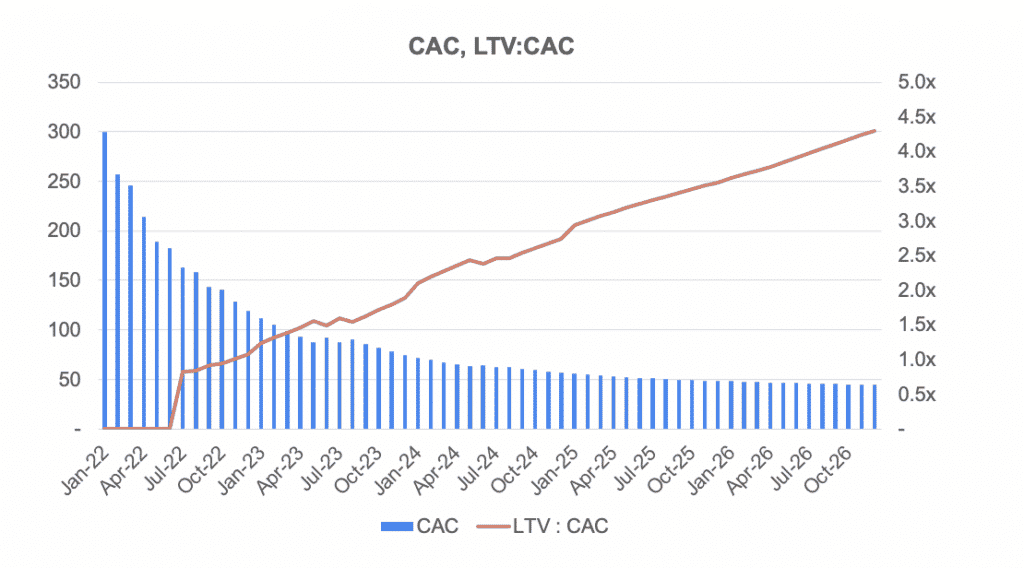

A common example are customer acquisition costs: the total cost, per new customer, a business incur to “acquire” and onboard one customer.

Let’s use our SaaS example again here. Let’s assume our SaaS business has a $500 customer lifetime value (“CLV” or “LTV”) yet spends in average $500 per new customer (CAC). It’s obviously losing money (as other expenses reduce further the overall business margins, therefore negative).

Yet, if one doesn’t have a clear idea of what the LTV actually is, one can easily overspend in CAC to get more customers. In such case, growth at all costs is unprofitable.

Note: Startups sometimes spend more in CAC than their LTV, and it’s ok. Often, they don’t have yet a clear idea of what their LTV actually is. Sometimes, it’s to gain scale and/or find product-market-fit. As long as LTV is carefully monitored, it’s ok. Yet, founders shouldn’t rely on this strategy for too long, at the risk of failing to raise future rounds, and eventually bankruptcy.

To increase your startup valuation, show investors your startup’s growth is both positive net of churn and profitable.

#3: Maximise sales predictability

As we said earlier, the lower the risk, the more valuable a business is. Therefore, it doesn’t come as a surprise that higher predictability is synonym with higher multiple.

Subscription business models

When it comes to predictability, sales (or revenues) first comes to mind. That explains why we’ve such a surge in subscription businesses over the past few years.

And this isn’t just in software SaaS, but also existing businesses pivoting from one-off transaction to subscription revenue models. One great example of the latter is the emergence of subscription ecommerce business models recently.

Logically, subscription businesses have a great edge here: the lower their churn, the more predictable their sales are. This is why SaaS and other subscription businesses typically have some of the highest valuation multiples across industries.

Non-subscription businesses

Luckily for other founders, sales predictability isn’t limited to subscription and SaaS businesses. Businesses with a significant and increasing part of their revenues being recurring (or “repeat”) also get significantly higher valuation multiples.

For example, one marketplace with 20% of its sales coming from repeat customers is de facto more valuable vs. another with 10% repeat sales only (all other things being equal).

Same goes for ecommerce businesses: the more retention they create, the more valuable they are.

When looking at your sales predictability, you should be familiar with repeat customers, churn, purchase frequency and customer lifetime value. Understanding these terms will allow you to assess your business sales predictability and, potentially, get a higher multiple from your negotiations with investors.

Therefore, in order to increase your startup valuation, maximise the portion of your business’ revenues that are recurring (or repeat).

#4: Show Scalability

For startups, unit economics are metrics (operational e.g. users or financial e.g. revenue) that are calculated on a per-unit basis. Often, the unit is a customer or user. But it can also be:

- Average Revenue Per User (ARPU)

- Customer Acquisition Cost (CAC)

- Customer Lifetime Value (LTV)

- Average video streamed length per user (for companies like Youtube)

- Total transaction volume (for Fintech companies)

- Etc.

Investors care a great deal about unit economics, especially Series A+ investors (as explained in our article here). Indeed, unit economics are the best way to assess and forecast a business’ profitability.

Yet, before businesses actually become profitable, they need to be scalable.

Indeed, your startup might not be profitable for the next 3 to 5 years as you scale up and invest in growth. Yet, the money you invest needs to be enable scalability. Scalability is a powerful multiple booster because it allows for businesses to scale profitably.

Let’s use 2 examples below to understand the difference between profitability and scalability:

- If for every $10 you invest you get $100, you are profitable but not scalable

- If you invest $10 and get $100, and another $10 that get you $101 (for example), you are profitable and scalable

Another good example is the famous LTV:CAC ratio. We already mentioned LTV and CAC earlier, looking at the ratio between the 2 tells us how profitable a business’ acquisition actually is.

For example, it makes sense to spend $500 to onboard a customer if you can reasonably expect this customer to bring you $2000 over her/his lifetime. It’s ok if you’re loss making today (as you’re incurring other fixed expenses like salaries and rent), as long as your LTV:CAC ratio above 2-3x (depending on the type of business).

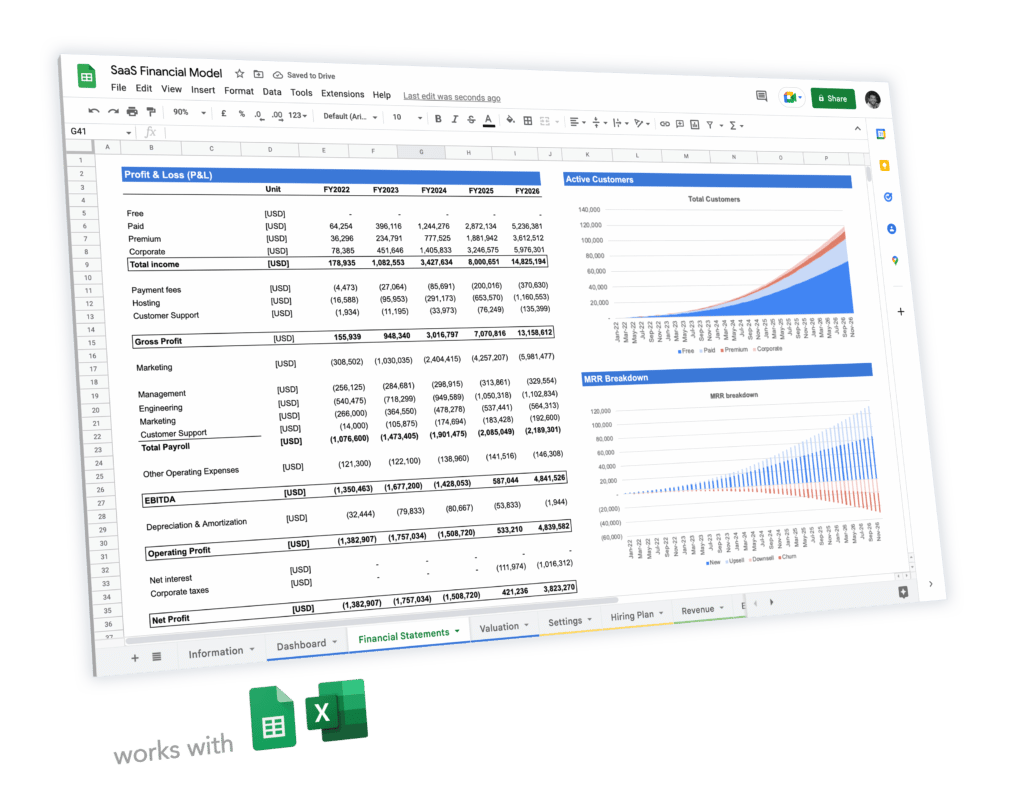

5-year pro forma financial model

5-year pro forma financial model 20+ charts and business valuation

20+ charts and business valuation  Free support

Free support